Okay this is a long one so I’ll get right into it. But first let me make two points:

It’s not escaped my attention that these articles have been getting longer. I pledge to try and make them shorter from here on out (though this one was always going to be a biggie).

A fractal is a geometric shape with an infinite level of iterative detail which replicates at every scale. Much like an act structure. It also contains the word “act”, so it’s a play on words.

I find that the best jokes require a detailed explanation.

Let’s crack on.

WHAT IS AN ACT AND WHY DO THEY MATTER?

Acts are the big chapters of your story. They’re discrete blocks of narrative that end in a natural break point - a moment where something significant changes.

In broadcast television, acts are dictated by commercial breaks. That gives you some sense of their purpose. You’re dialled in for a single, cohesive chunk of story. Then at some point you’ll be given the opportunity to blink, breathe, maybe take a pee, before you’re back into it for the next act.

But the main reason they matter is because people talk a lot about acts. They can seem intimidating, confusing, irrational. And we’re about to find out why.

There are a lot of ways to slice this particular pie, so strap in.

ONE ACT

This is largely the domain of theatre. But you could also think of a short film, a sketch, or even a joke as one act.

Essentially a one-act presents one unit of action. A single line of conflict that builds to a climax. There’s not a great deal of room for reversals or major escalations that take things in a new direction.

You could add more acts to a short film, but it’s not necessary and actually not ideal. As a general rule of thumb, the simpler you keep the plot, the more complexity you can add.

Complication and complexity are two different things. Complication adds surface-level elements - more characters, more plot points, more “business”. Complexity goes deep, exploring different facets and shades of a character or dramatic scenario.

You need both to some degree. But more complexity is always preferable to more complication.

I’m getting side tracked. Point is you’ll never see a one-act feature film or TV episode. And if you do find one, probably don’t watch it.

TWO ACTS

We’re still in the realm of theatre. Classically plays would consist of two acts with an interval in the middle so the audience can get a drink at the bar.

The interval would also give the production a chance to change the set, costumes, etc. So a two-act play traditionally provides a structure where the two major units of action occur at different times or places.

The switch-up in the middle breathes new energy into the story, and allows for various stagey conceits.

Some films are structured around two halves so distinct from each other that they feel like two acts.

Films like Full Metal Jacket; A Place Beyond The Pines; Psycho; Atonement; Mulholland Drive.

But if you’re writing a feature script or a pilot, the two-act structure needn’t concern you any more than the one-act.

THREE ACTS

Here we go. The OG. The daddy. The big banana.

The act structure that every other act structure, to some degree or another, is built upon.

Why? Because the three-act is the first to feel like a story as we experience it.

At this stage I should point out that the dividing lines between the acts (act breaks) are as important as the acts themselves. They are the pivot-points that throw you from one act into the next.

A three-act structure is generally laid out something like this:

ACT ONE: Introduction

(act break: inciting incident)

ACT TWO: Rising action

(act break: climax)

ACT THREE: Resolution

But in my opinion it’s more intuitive to think of it like this:

ACT ONE: Equilibrium

ACT TWO: Disequilibrium

ACT THREE: New Equilibrium

This approach more closely mirrors that story experience I mentioned above.

Act one - we meet your protagonist in a state of (imperfect) balance. If they did nothing, they would continue to go about their daily life indefinitely. They could take no action whatsoever and nothing would change.

Act three - After all that big bru-ha-ha, everything re-settles into a new equilibrium. Things have fundamentally changed, but again the protagonist is back in a place where everything would tootle along just fine if they did nothing meaningful. The proverbial “happily ever after”.

Act two - every moment in act two is unbalanced, unstable, unsustainable. Your protagonist has to act to resolve their immediate scenario. They can’t simply stop what they’re doing and return to their old equilibrium. Nor can they vault forward to their new equilibrium. They have to constantly manage their current unbalanced state.

This gives you a sense of the kind of momentum you need to maintain throughout your second act. Your protagonist must always be negotiating a scenario that needs their attention. Because not acting will only make things much worse.

From an unhealthy situationship with a hot-but-toxic musician, to a rival army preparing for pitched battle, act two scenarios are volatile, unsustainable, and demand action.

There’s a problem with the three-act structure. The second act is loooong. In theory twice as long as the other two acts. In practice, often longer than that.

Helpfully, the three-act structure gives you a midpoint bang in the middle. The midpoint is a big whopper of a revelation, twist, or escalation of stakes. It casts the whole story in a harsh new light, and makes the first half of the story look like a children’s birthday party compared to what’s coming.

The midpoint should shake your characters to the core. It should make them realise that they’ve drifted into the very deep end of the pool - and their feet are very far from touching the floor.

This gives you, the writer, a useful waystation to switch things up in the midst of that long second act. But it does create the rather awkward substructure:

ACT ONE: Introduction

(inciting incident)

ACT TWO A: Rising action

(midpoint)

ACT TWO B: More rising action

(climax)

ACT THREE: Resolution

Parts A and B? Not ideal. Don’t fear: there’s an act structure for that.

FOUR ACTS

The four-act structure essentially creates a new act break at the midpoint. And rightly so in my opinion. How does the biggest plot point in the story not deserve it’s own act break? Justice for the midpoint.

You can also reframe the terminology to make the whole thing a bit more graspable:

ACT ONE: Introduction

ACT TWO: Rising action

ACT THREE: Crisis

ACT FOUR: Climax

This probably reflects the shape and “viewing experience” of your typical film more closely than the three act structure.

The three-act structure’s “resolution” can trip people up. Because we think of resolution as the moment when everyone says “phew! Thank god we sorted all that out.” When in fact it means the process of resolving all the mini and major conflicts.

Climax, in the four-act structure, accurately describes the feeling of modern films. In which the big intense action - or the climactic confrontation - takes us all the way to the end of the film, or near as.

Splitting the second act into two also gives each one its own distinct characteristic, which again more accurately reflects how things shake out.

Act three, formerly 2B, is where the antagonist starts to take the upper hand, and everything gets more serious. It’s the stretch after the midpoint, before everything comes to a head.

FIVE ACTS

The five-act structure adds two kind of shoulder acts into the three-act structure. It provides more undulations, and further drills into the psychology of storytelling. In my opinion it’s the better for it.

You’ll see how it maps over the three act structure:

ACT ONE: Introduction

ACT TWO: “Refusal of the call”

ACT THREE: Rising action

ACT FOUR: “All is lost”

ACT FIVE: Climax

Acts two and four are shorter than the others, and seem oddly specific. But they are common - and useful - enough to merit their own dedicated acts.

The refusal of the call provides a moment for the protagonist to reject a major offer, ignore a looming crisis, or generally resist forward progression.

What this means is your protagonist can make their first major active choice, when - after refusing the call - they choose to accept the call, to step into the story. It’s a moment to show the goals, flaws, and values of your protagonist in action. They are under real pressure for the first time, and they act.

Act two also splits the inciting incident into two pieces (the act breaks before and after act two). An inciting incident is of course the major event that throws your protagonist into their story - (except, per the point above, they’re not passively thrown into their story but actively resist, then actively choose to enter it).

An inciting incident can present as a crisis (your daughter’s been kidnapped) or an opportunity (a casino cash truck is rolling through town tomorrow).

The five act structure highlights the fact that the inciting incident is often made up of a crisis and an opportunity (your daughter’s been kidnapped; they’re demanding a ransom; a casino cash truck is rolling through town tomorrow).

The other new addition is act four, the “all is lost” moment, which I wrote about here.

Briefly:

Stories thrive on contrast. They want to exist in the extremes, not the middle ground. So what better event to place right before the biggest and most conclusive win of the whole thing? The biggest and most conclusive loss of the whole thing.

The problem with the five act structure? It whips the act break away from the midpoint again to reinstate that oversized third act.

SIX ACTS

This is the structure I use in practice. It doesn’t really exist as an act structure in its own right. But I pull a “four-act” on the five-act structure, and add an act break back into the midpoint.

This creates two separate acts out of act three, and spaces everything out a bit more equally.

So it looks something like this:

ACT ONE: Introduction

(crisis)

ACT TWO: Refusal of the call

(opportunity)

ACT THREE: Rising action

(midpoint)

ACT FOUR: Sh*t gets serious

(crisis)

ACT FIVE: All is lost

(rally)

ACT SIX: Climax

Incidentally, you can swap the crisis and the opportunity round, if it better suits your story.

At some point in whatever script I’m writing, I will use this as a template to see how things line up. As with all of these act structures, it’s a useful diagnostic tool rather than it is a doctrine to live by.

But I find this to be the ideal balance between too much and not enough. There’s enough complication there to push the story along, but plenty of space to add complexity.

This is the shape I would use to go deep on the science and psychology of story. And maybe one day i will.

Are you still with me? Because we’ve got plenty more act structures to go.

To be fair to the creators from here on out, none of the following structures refer to acts as “acts”. They’re sequences or plot points or beats.

But these are pitched as the fundamental architecture of a story, built from immutable segments. So they’re acts in everything but name.

Onwards, into the weird, wonderful, and unnecessary…

SEVEN ACTS

Usually ascribed to Dan Wells and labelled a “7-point” story structure, the seven-act is actually just my beloved six act structure, but Mr Wells chooses to identify the turning points // act breaks rather than the acts themselves.

He lists them like this:

Hook

Plot turn 1

Pinch point 1

Midpoint

Pinch point 2

Plot turn 2

Resolution

Again, Mr Wells uses the imperfect “resolution” to denote the climactic action of a story. Also, what’s a hook? How is a plot turn different to a pinch point?

I’m sure it all makes sense if you dive into it. But at this stage you might be better served scanning back through earlier act structures to get a handle on this one.

(And if you haven’t figured it out yet, I’m building a thesis here…they’re all kind of the same thing).

At least our old reliable midpoint is still present and correct.

EIGHT ACTS

The eight- act sequence structure can be draped over the four-act structure with mathematical precision, as seen here with the story breakdown of The World’s End by Simon Pegg and Edgar Wright:

This image does a fine job of filling in the blanks, so I’ll spare you a detailed rundown of the eight-sequence structure.

Suffice to say it adds a more handles for you to grab onto, which can be useful or constricting depending on your own personal MO. It’s also fairly prescriptive - valuable if you’re writing a certain kind of story; less so if you’re not.

Incidentally Dan Harmon’s much-loved story circle also consists of eight sequences, so maybe there’s something to this eight-part business.

NINE ACTS

The numerically minded of you will have already surmised that the nine-act structure maps perfectly over the three-act structure.

Like the eight-sequence structure, it simply adds more waystations to guide // constrict you.

Another way of looking at the nine-act structure is through the lens of the five-act. It keeps acts one, two, four & five, but splits act three into a whopping four separate acts. Basically turning every pressure point, gear shift, or escalation into its own act break.

You can find it out there on the internet if you really want to. Although honestly if you haven’t found an act structure that works for you so far…maybe give the writing a rest for now.

Cross-eyed yet? I have good news. Ten- and eleven-act structures are in mercifully short supply.

But we come thumping back with:

TWELVE ACTS

And believe it or not, this is another biggie. Because it’s none other than Joseph Campbell’s fabled Hero’s Journey.

Almost as venerated as the three-act structure, the Hero’s Journey is a whole thing that, yes, very strongly echoes other simpler act structures, but adds a boatload of other elements.

When outlining the Hero’s Journey, the same references are often used - Star Wars; The Lord of the Rings; The Wizard of Oz. There’s a reason for that.

It’s better suited to a certain kind of quest or “personal crucible” story. Many attempts have been made to apply it to more contemporary films. But it all starts to look a bit woolly and nebulous and frankly not as intuitive as other act structures.

Look, we’re all tired. And as I said Campbell added all kinds of fiddly business like mentors, and treasures, and supreme ordeals. I’m just going to put a primer here if you want to explore it more.

THE 10×10 // 12% // WHAMMY STRUCTURE

And finally, a bucket of very similar structures that all kind of do the same thing.

Essentially: add something of interest every ten-to-twelve pages. A new character, a new location, a revelation, twist, escalation…a whammy.

This is surprisingly great for a certain kind of story with a certain kind of pace and feel to it. Think thriller, horror, action-adventure…

I’ve used what I call the 10×10 structure (10x10-page acts) to great effect. It’s been ascribed to Joel Silver and thus was forged in the furnace of actual movie-making.

Like everything that seasoned producers come up with, it works in practice even if the narrative theory behind it isn’t as robust as, say, Campbell’s monomyth business.

And I like things that work in practice.

Again, if your story is operating at a certain register, it can be a useful diagnostic tool to trim fat, or add heft where needed.

I’m not suggesting every single important turn needs to land at the exact ten-page point. But something of interest roughly every ten minutes is sure to hold a viewer’s attention. Just so long as it delivers on all the other stuff.

So what have we learned?

Well, there are a lot of act structures out there.

But if you squint and blur your eyes a bit, the same patterns and story events recur over and over again. They are, when you get down to it, increasingly intricate manifestations of the same fundamental shape.

Like a fractal.

They only really exist to describe what’s present in every well constructed story. They are in effect different analogies trying to shed light on the same thing.

The only reason I’d advise you to study these act structures (and any others you find in the wild), is to develop a bone-deep grasp of what really underpins all stories.

By reading the same thing over again in different guises, you’ll internalise the rhythm of story. You’ll start applying it naturally, subconsciously, instinctively.

You’ll develop a knack for what goes where. Your scripts will become stronger and more robust, and you won’t need to tear them apart as frequently, or give up on them completely.

It’s a kind of “need to learn it so you can forget it all” situation.

Plus now you know that all act structures are basically doing the same thing, it’s one less thing to worry about.

And if there’s anything we need in this world right now, it’s one less thing to worry about.

Thanks for reading.

Till next Tuesday, go get after it.

Rob

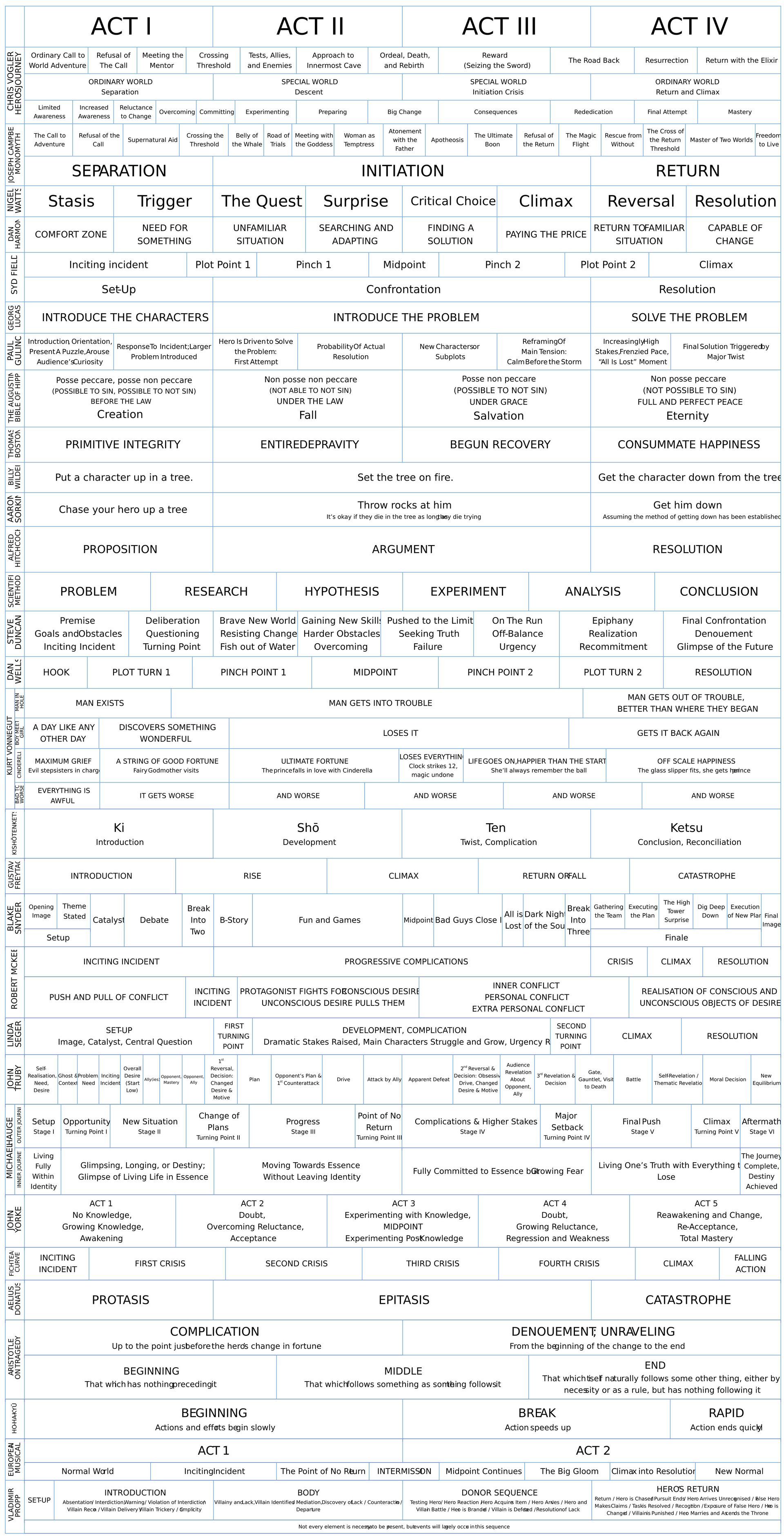

P.S. If you can’t be bothered to read the same thing over and over again, here’s a handy cheat sheet (that also conveniently goes a fair way to proving my thesis).

All the acts you’ll ever need