What do we mean by intrigue? Anything that makes the reader sit forward and pay more attention; anything creates an immediate craving for a certain kind of resolution.

Intrigue is synonymous with secrets, hidden agendas, illicit meetings - in other words, any scenario in which information is withheld or manipulated.

It all comes down to what we’re showing, when, and why.

I wrote a few weeks ago about how posing a question creates chaos in a viewer’s mind, and only answering that question will bring the order our lizard brains demand.

Today I’m going to take the idea further, looking at how we can manipulate information to toy with the viewer - and keep them leaning in till the end.

Plenty of films lay out every piece of information the viewer needs in a direct, linear fashion. No funny business. It doesn’t necessarily suit some films to withhold, tease, or otherwise mess around with the order in which we learn things.

But much of the time - in fact I would say the vast majority of the time - creating some level of intrigue is going to do wonderful things for your script.

The idea of intrigue feels woolly and vague. But it actually breaks down into three neat categories.

As always, identifying something is half the work of conquering it. Knowing these categories, recognising them in the things you watch and read, and mastering them yourself, can seriously level-up your writing.

So lets not hang around.

Side-note: I’m going to talk in terms of the viewer, because lets live in a world where all our scripts get made into films and TV shows. But obviously “viewer” is interchangeable with “reader” if we’re talking about getting things down on the page.

MYSTERY

Mystery is any scenario in which a character knows more than the viewer.

Consider Get Out. Our protagonist is Chris, played by Daniel Kaluuya. Chris really has no clue what he’s walking into. He believes he’s simply going to spend the weekend with his girlfriend’s parents.

When seriously weird stuff starts to go down, he has no idea what to make of it.

His girlfriend Rose and her parents however know exactly what’s going on from the very beginning. Crucially, they are POV characters along with Chris. And so we spend time in a state of disconnect: several key characters hold all the cards, and yet we (along with Chris) are completely in the dark.

We’re witnessing strange moments, odd behaviours, details we can’t make sense of. We know there are answers. We know that these characters have the answers. We just don’t have the answers ourselves - yet. And darn it if we aren’t going to stick around to get them.

This disconnect creates a pervasive sense of mystery that sustains till the final act.

There are literally thousands of examples of mystery in popular culture. It’s common in a certain kind of puzzle-box horror like Longlegs, Midsommar, or The Wicker Man.

And of course it’s indelible to detective thrillers and (as the name would suggest) murder mysteries.

In a murder mystery, we always spend time with the killer (we just don’t know who it is). They know they did it; we don’t. The cryptic snippets of information we collect only serve to highlight how occluded the full picture is; how little we know. That’s what generates the sense of mystery.

What’s more, the detective is often one or two steps ahead of us. As things move towards a climax, the detective puts the final pieces together and races to gather all the suspects in a room and offer their final damning verdict.

This sequence is the essence of the mystery. Our protagonist now has all the information, and it’s carefully, tantalisingly doled out to us.

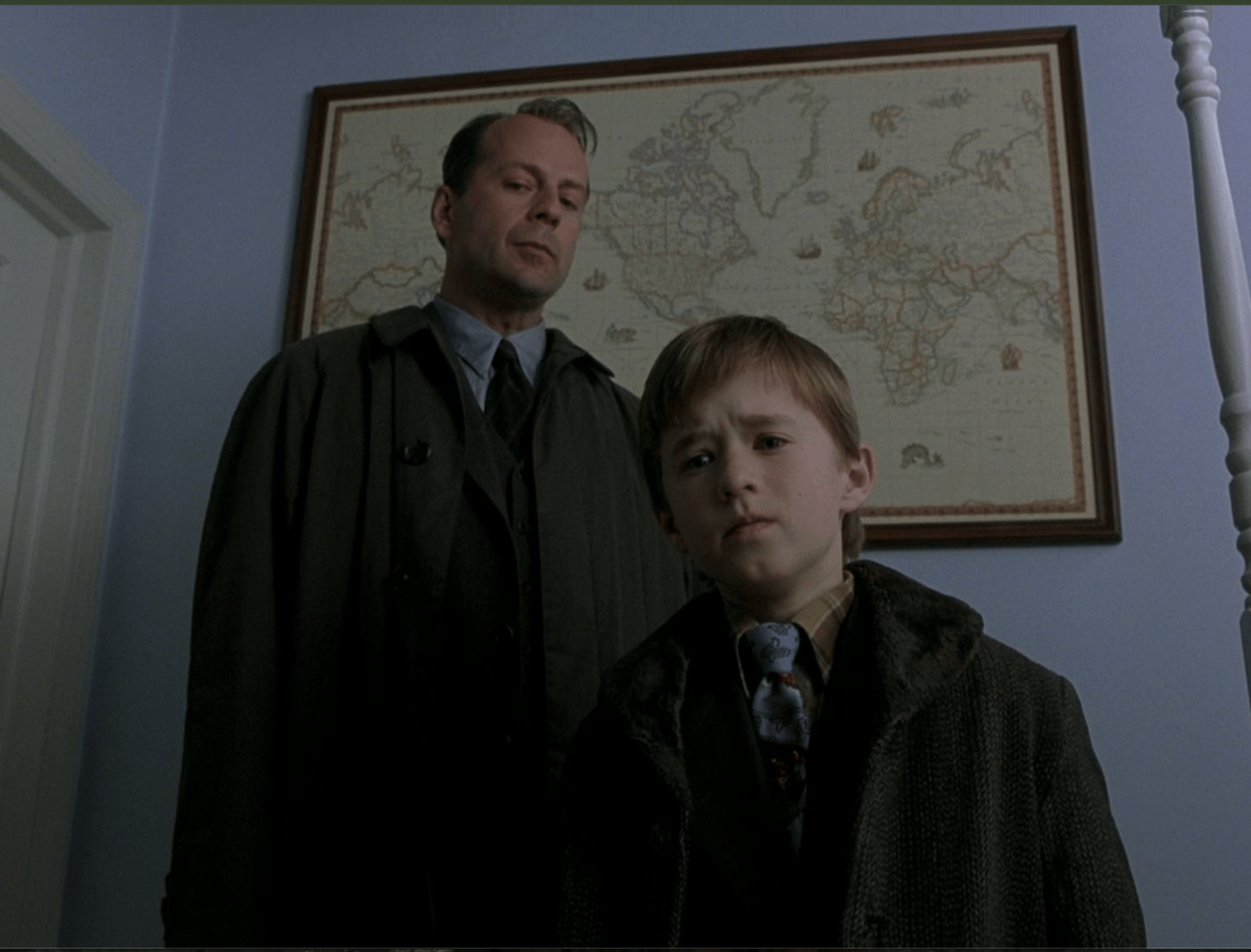

The Sixth Sense - a film that plays artfully with the line between mystery and suspense

More on mystery:

Any time a character says something like “…and I know just the man for the job.” Or “…and there’s only one place on Earth we can find it.” before cutting away to a subplot, that’s mystery. The character knows to what they refer; we don’t. We have to hang around to find out.

Mystery helps create a sense of authorship, of orchestration. The writer is telling the viewer - there’s more to discover. Pay attention and your curiosity will be rewarded. We’re really going somewhere here.

Dropping a little bit of mystery into a relatively safe and straight-forward stretch of story can prevent a viewer slipping into autopilot, or tuning out completely. It’s like clicking your fingers in their face and saying hey: pay attention.

Its why “flash-forwards” are so popular. How many films open on a dramatic scene that builds to a cliffhanger, before hitting you with “One Week Earlier”.

The characters know what their situation is; we don’t. The film has fabricated a little mystery to pull you through the expositional first act.

Mystery can also help build a character who feels capable and full of agency. They are leading the way with their information, their planning, their powers of deduction. We’re being pulled along for the ride. We’re swept up in their wake as they act on information we don’t yet have.

Midsommar - the kind of face you pull when you push for answers, then wish you didn’t

SUSPENSE

Suspense is created when a character knows the same amount as the viewer.

Where suspense is at play, we are much more closely aligned with our character. Effectively shoulder-to-shoulder with them, learning as they do. We’re in it together. This creates more of a real-time, immersive experience.

Imagine your protagonist moving through a dark house - or a drug den - entering each room without knowing what they’re going to find.

Or trying to decrypt a bomb. We don’t know the code; they don’t know the code. That’s suspense.

It is an immediate, edge-of-your-seat type sensation. No-one is in charge here. No-one’s pulling the strings. Not the writer, not the character, not us. We’re all barreling forward, running blind, alert to any hint of danger.

Suspense can be unbearable at times. You can hardly watch, but you can’t stand to look away. It’s a crucial component in thrillers and horror - and the ideal recipe for a sudden shock, like a jump scare.

The Truman Show builds its whole premise around dramatic irony

DRAMATIC IRONY

Dramatic irony describes any scenario in which a character knows less than the viewer.

We, the viewer, are ahead of them in some way. They’re the ones in the dark and we’re the ones with the information. Doesn’t sound very intriguing, does it? We’re always told that the viewer should never get ahead of the story.

But if you’ve ever shouted “don’t open that door!” at the screen, you’ll know that dramatic irony can be one of the most powerful tools in a writer’s toolbox.

Going back to our protagonist moving through the drug den. If we know that in the rear bedroom there’s a ruthless thug with a shotgun primed at the door, watching the protagonist checking room after room becomes all the more tense.

We know the violent confrontation is coming - they don’t - this builds a certain kind of tension you can’t achieve through mystery or suspense.

Alfred Hitchcock’s famous “bomb under the table” theory of suspense is actually an example of dramatic irony.

Again, we know the bomb is under the table, the characters don’t. The torturous anticipation of the bomb exploding is ratcheted up because they don’t know. They have no sense of urgency or stakes, which somehow makes it all the more tense.

This theory is usually used to explain the difference between surprise and suspense. I’m being pedantic by saying actually its an example of dramatic irony. Which some people would say is a form of suspense…

It all gets a bit nebulous. As last week’s article on acts highlighted, this is a common theme in screenwriting. Terms and ideas kind of melt together and needlessly separate and sometimes reappear under different names.

I believe in this case it’s worth separating out these terms. The more we can appreciate them as distinct elements, the more effectively we can use them in our scripts.

So be pedantic with me. I’ll never tell you how to write, or what to write. But I will be a nerd stickler for all the different techniques you can use to write better.

A final point on dramatic irony, it often generates a sense of tragedy or melodrama, lifting proceedings to new emotional heights. Consider Titanic. A whole two hours of dramatic irony underpins Jack and Rose’s (doomed) romance.

I’m going to finish with one mega-example that artfully weaves all of these threads together.

“WHAT’S IN THE BOX??” It’s no coincidence that Se7en’s most famous quote is a question

Let’s talk about Se7en.

Why? Because it’s one of my favourite films of all time. But also because it’s a compelling case study in the three levels of intrigue.

Going back to nebulous terminology, Se7en feels like a mystery. It wouldn’t be out of order to describe Se7en as a mystery.

But unlike most detective thrillers, Se7en lives in suspense.

At no point do our two detectives know more information than us. We watch them learn that they’re being partnered up. We watch them roll up on every murder scene. We experience it along with them. We find the clues as they find the clues. We see them perplexed, frustrated, repulsed by what they’re witnessing.

We’re in the room as Dt Somerset puts the pieces together: seven murders, seven deadly sins. And when John Doe finally turns himself in, they’re as bewildered as we are.

Compounding this, we spend no time with the killer alone. We don’t see him prepping his murders, choosing his victims, anything like that. John Doe is not a POV character. The engineer of these atrocities remains unknown to us for the majority of the runtime.

So the entire action of the film plays out in the immediate reality of the two cops trying to end this murder spree - a state of suspense. Until the final act, we’re never with a character who knows more than we do.

And yet as the iconic finale stalks up on us, writer Andrew Kevin Walker finds ways of pulling the other levers of intrigue.

The final fifteen minutes of the film. They have John Doe on his knees in cuffs, out in the scrubland. Dt Mills has a gun trained point-blank at his head.

SUSPENSE: A delivery van rolls up. Dt Somerset hurries over to figure out what’s going on. He doesn’t know any more than we do. Even the delivery driver has no clue what’s going on. Mills looks equally perplexed from afar.

None of the characters we’re with is ahead of us here. We’re all moving through the scene together.

Well, except one.

MYSTERY: We’re now with John Doe. He talks cryptically, clearly knowing more than we do. He is a mysterious figure, deliberately withholding his knowledge from Mills, and from us. Drip-feeding information as he taunts his final victim.

Then Somerset opens the box. The fullness of the horror is revealed to him - but him alone. We don’t see what’s in that box.

Thus he too has moved into a mode of mystery as he screams to Mills “Put the gun down!” He knows why he’s suddenly so agitated. John Doe knows. But Mills doesn’t. And neither do we. The dial has fully shifted from suspense to mystery. And it will remain there until we hear those chilling words: “Her pretty head.”

DRAMATIC IRONY: Earlier in the film Somerset learns that Mills’ wife is pregnant. We learn it too. Mills does not.

Mills doesn’t find out until the final appalling revelation. This thread of dramatic irony cranks up the tragedy of the final act.

Not only is Mills uninformed about what’s going on, he has no idea just how much he’s about to lose in a single dreadful revelation. This pushes the closing moments to almost operatic levels of emotional anguish.

There are few gut-punches like it in cinema. And unquestionably this element of dramatic irony as a key part of its impact. We feel it all the more acutely because we know, and Mills doesn’t…until he does.

One last shout out for my four-question Google form before I retire it.

I will start fashioning articles around what you told me you want to read here, so it’s your last chance to have your say.

Next week, I’m getting ghoulish with a guide to writing horror.

Since we’re dealing with scene structure this week, I’ll leave you with an article from screenwriter and director Tony Tost.

It’s within striking distance of my article on scene dynamics. But Tony frames it rather pleasingly as “the shape and the juice”. The kind of perspective you only really get from working writers.

Thanks for reading.

Till next Tuesday, go get after it.

Rob