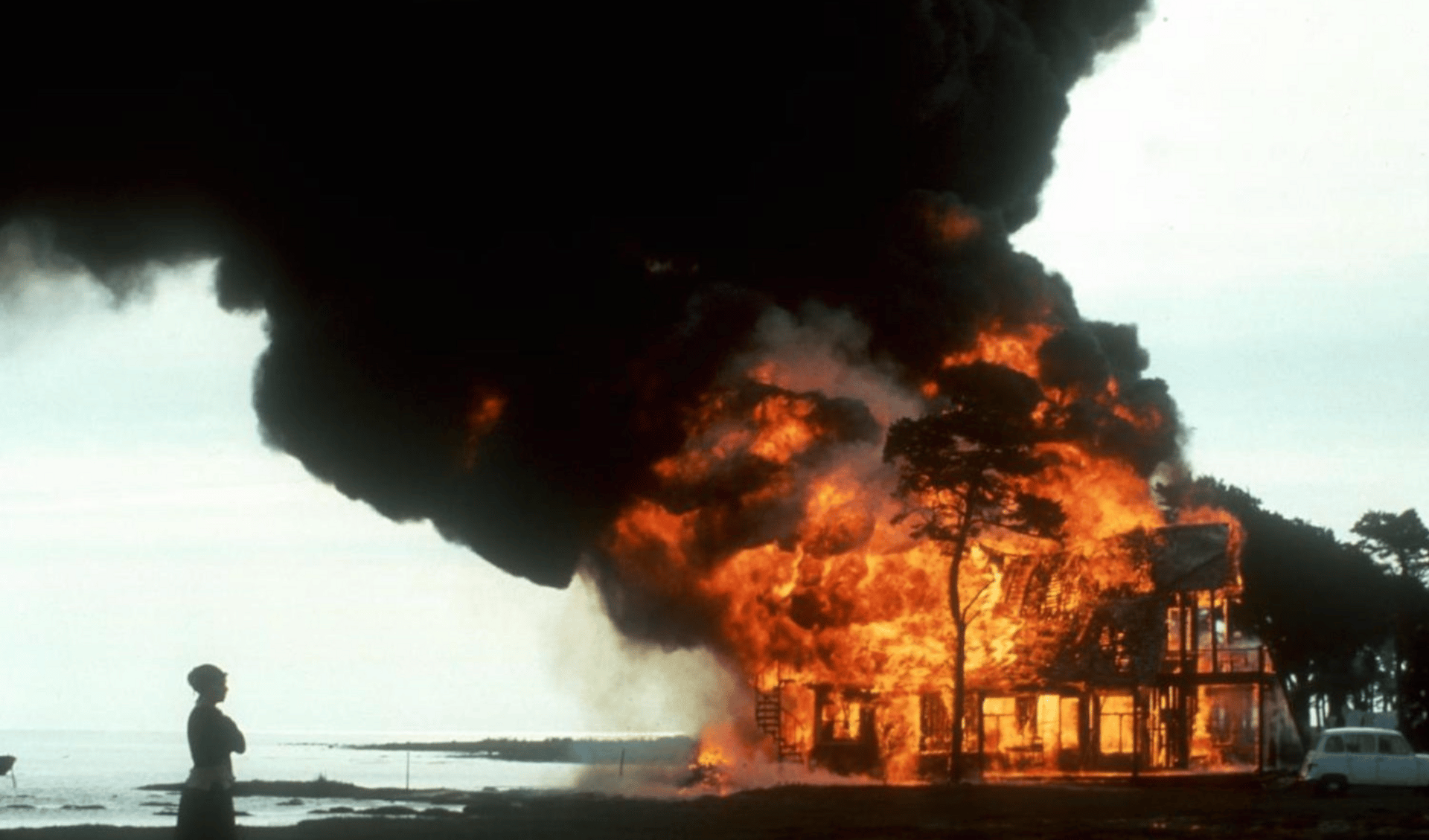

Andrei Tarkovsky’s The Sacrifice - the man knew how to burn down a house

Of all the unproduced scripts I read, I’d say 8/10 of them share the same problem.

They go too easy on their protagonist.

As a result, the whole story kind of feels like a shrug.

To paraphrase screenwriter John August: If telling your protagonist’s story is like building them a house. Before the end, you need to burn that sucker down to the ground.

Most writers spend their whole story building a house, but they can never quite bring themselves to burn it down.

Quick anecdote. I was in the writers room for the limited series Stags. We were into our last week. We were tired. Poor Daniel, the head writer and creator, was in something of an existential funk.

We were so close to the end - breaking the last episode - and he seemed to have lost all sense of what he was trying to create. Tone, plot, character…it was all slipping out of his grasp.

The scene we were working on was this:

Our protagonist Stu is trying to escape a prison island with his most loyal best friend, Ryan. A lot of gnarly stuff has gone down. They are the last two surviving members of their doomed stag party.

Stu, we knew, was inherently villainous. We also knew he needed to get off the island. Beyond that we were all stumped. We’d lost our mojo.

Then I made a pitch:

Stu and Ryan find a single life jacket. Stu desperately wants it for himself. But he’s with his best mate.

He proceeds to kill Ryan, right there on the beach, in order to escape with the life jacket. It’s a savage moment. Stu’s worst act by far.

Then he pulls the rip cord to inflate the life jacket…only to discover it’s an 8-person inflatable dinghy. Plenty of room for them both to have escaped.

That was the pitch.

Daniel’s eyes lit up. He literally got to his feet and hugged me like he’s just won the lottery. He talked about that one breakthrough for the whole rest of the process.

Why?

It took me a minute to realise I’d given Stu his all is lost moment. His worst point. His dark night of the soul.

All Stu’s external goals had already burned down. The wealthy father-in-law he was trying to impress (shout out to last week’s article) had perished. His wedding was called off. The drug stash he’d been trying to smuggle home was in the wind.

So what did this life jacket // dinghy moment do for him? It destroyed his internal goal - to believe in himself that he was fundamentally a good person; that all the terrible stuff he’d done, it was all down to circumstance, and not because of his toxic personality.

Stu’s entire identity was built on the false belief that he was inherently good. It was the last thing we needed to take away from him. Killing his best friend to save his own skin, then realising it was a futile act? That destroyed the last load-bearing pillar in his burning house.

And it set him free to discover his true need - to survive this hellhole at all costs.

I should point out that structurally, Stu’s journey was a villain arc. He needed to embrace his villainy to succeed.

But the point illustrates how bad things have to get in the moments just before the climax of your story.

Side note: if this anecdote sounds like I’m tooting my own horn, I am. But don’t worry, the humbling was coming for me - in the form of 17 gruelling drafts that left none of our in-the-room genius moments intact.

A story for another day.

So. The all is lost moment.

A few weeks ago I wrote about the importance of having your protagonist lose as well as win.

Your all is lost moment is the big final loss - right before their final major win. It’s the point where the whole adventure // ordeal looks to have been for nothing.

The original goal that your protagonist set out to achieve now seems impossible. The values they’ve been shaping throughout the story are crumbling to dust.

Everything is just awful.

The worse this moment is for your protagonist, the better your ending will be.

And the better your ending is, the better your film will be.

That’s about as close as storytelling gets to a mathematical fact.

Okay, so…how?

How do you craft a massive, crushing loss - and still make the film as a whole feel like a win?

The answer is to ask yourself: what would your protagonist absolutely need to come away with, in order for this to feel like an ultimately positive experience?

Then ask: how can we pile on as many distracting shiny things as possible?

The more stuff we can give our protagonist, the more we have to take away at the all is lost moment.

But to achieve this, we need to know the absolute bedrock of what they need.

(Spoiler, it’s not what they first set out to achieve. We’re going to be taking that away from them too.)

Only when all the distractions are gone can your protagonist realise…oh, this was the only thing I ever needed.

Think of a rom-com. What your protagonist needs, really needs, is a life companion who will love her for who she is.

What does she collect along the way?

A head-rush of infatuation. Newfound confidence. A sharp new wardrobe. Meaningful progress in her stand-up comedy career // cake design business. A future mother-in-law who adores her. A satisfying triumph over her love-rival. A place of her own (after years of splitting the rent with her annoying housemate).

That’s all nice to have…but it’s not what she needs.

So take it all away. All of it.

We’re approaching the final act. She screws things up somehow, and her all is lost moment might look like this:

Her love interest hates her (because of the screw up)- and by extension so does the mother. Her love-rival has swooped in. She’s lost all confidence and is dressing schlubby again. She’s back living with her annoying flatmate - who now has an annoying boyfriend. With everything going on, she blows her one chance to impress a hotshot comedy agent. The head-rush of infatuation has been replaced with the brutal comedown of loneliness.

On top of that, she loses the actual galvanising belief that kicked off the whole story. Something like he’ll fall for me if I pretend to be someone else.

She’s not back at square one. She’s even further back than that.

Only when she’s this low, when so much good stuff has been taken from her, can she finally see the one thing that truly matters. The one thing still worth fighting for.

Because the only thing she needs is for her romantic partner to see her as she really is, and love her. If she can achieve that, she can still call this whole adventure a huge win.

Cue mad dash to the airport, interrupted wedding, endearingly off-the-cuff declaration of love, etc. etc.

And here’s the really sneaky hack…you can give it all back to them at the end! If it’s good for them and they’ve truly earned it by discovering what they truly need, they can have all the fun stuff too.

He’s a sample list of nice-to-haves you can rip out from under your protagonist:

Wealth

Fame

That big bag of diamonds

Cool new friends

The esteem of the entire community (school, workplace, sports team, neighbourhood)

A date with their crush (finally!)

An army of defeated bad guys

A place in the championship

A physical transformation

That major promotion

A sweet sports car

The forbidden treasures of Atlantis

The public humiliation of their high-school bully

An awesome mentor

A winning (but false) persona

The progress of all their stated goals so far

But that’s still not quite enough. Remember, we have to destroy the galvanising belief that kicked their story off to begin with. Here’s some examples:

I can and should change myself

I alone can save grandma’s retirement centre from being bulldozed

I can keep this lie up my whole life

Money will make me happy

Competitive air-hockey is the only thing that matters to me

If I become successful, everyone will like me

This person I’m obsessed with is definitely the love of my life

If I do what this shady criminal demands, he’ll surely let my family go free

Meanwhile, here’s a list of fundamental needs that will still feel like a win after everything else has been rudely snatched away (by you):

Self-acceptance

Teamwork

A “found family”

New insights into human nature (good or bad)

True love

Humility

A sense of belonging

The strength to lay old demons to rest

Genuine forgiveness

Saving the world

Saving a loved one

A proper work // life balance

Control over, and responsibility for, one’s own actions

If some of these things sound cheesy or cliché…welcome to the movies, baby!

In all seriousness, for the most part viewers want a film to affirm the values they recognise to be true and good. The key is to earn the slightly trite message by putting your characters through Hell in order to arrive there.

As I get older I’m realising this is what I love most about movies. They exist to remind us about the pure and honest aspects of life. The priorities that matter. The things we should really cherish.

The world is a better place when mainstream movies are at the centre of our culture.

Don’t get me wrong, I love a nihilistic bruiser as much as anyone. Give me Requiem For A Dream or Saw any day. Just not every day. Because it’s best in small doses, to wake up the palate. Same principle that makes salted caramel taste so good.

As an exercise, take a look at the protagonist in the story you’re currently writing. Ask yourself:

What is the fundamental need that they have to satisfy to win the story?

What fun-to-haves can I pile on top to disguise this, then burn down? What galvanising belief needs to go down in flames along with them?

There’s more to say about putting your protagonist through Hell (it’s an important topic). But I’ll save that for another article.

While I’m here, I’ve got a couple of things to share.

First is step four of Beginner to Pro over on the website. This time, we’re going from logline to first draft.

Second, I heard about the Stunt List a few years ago. I thought it was like the Black List but for action films.

Turns out, the scripts themselves are the stunts.

It’s a list of scripts that can be considered wild swings. They stand almost no chance of getting made, but their sheer bravura nature hijacks industry attention and hopefully leads to future work for the writer.

It’s a tried-and-true method of gaining traction. And I touched upon the growing need for taking big swings here.

Disclaimer: this is not an endorsement of the quality of these scripts. I read one that was meh, one that was solid, and one that I thought was great. So proceed at your own risk.

But take a look. Hopefully something on there will inspire you to stay true to your own unique voice and vision.

Hey, maybe that’s your fundamental need.

And that, fellow writer, is called a button.

Thanks for reading. Go get after it.

Rob